"Can I Touch It?” The Story Behind Endia Beal’s Hair-Raising Photo Series

Published Jan 18, 2014

They were the four words that changed everything: “Can I touch it?”

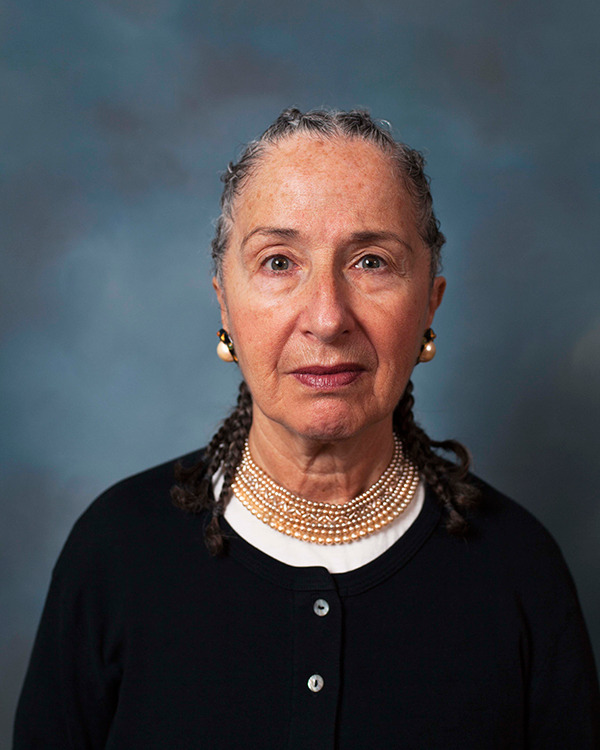

While studying for her MFA in photography at Yale University, artist Endia Beal found herself in a peculiar situation. Her internship in the school’s IT department had her working alongside many middle-aged white men who were quietly in awe of Beal, a stunning black woman who stands 5-foot-10 and possesses what she calls a “floating afro” that peeked out above the cubicle walls.

“One of my co-workers confided in me and said, ‘A few of the guys have been talking about wanting to touch your hair,” the North Carolina resident recalls. “I was intrigued. Here this conversation was secretly happening around me, but I wasn’t included in the dialogue.”

Rather than be offended, Beal embraced her colleagues’ curiosity head on and tried to figure out a way she could use the experience in her art, which often focuses on invisible and marginalized documentary subjects (her previous work has included a profile of a group of Senegalese immigrants and another of fake handbag vendors in Italy).

So Beal set up two cameras in the office, and allowed the men to touch my hair. “But I didn’t want them to just touch my hair; I wanted them to pull it, grab it, and feel it. I came back a week later and interviewed them about the experience,” she says, noting they all stated that it made them uncomfortable. “That was the goal though—making the uncomfortable comfortable,” Beal explains.

That experiment, and the dialogue that continued over the span of a year after (particularly among female colleagues), inspired Beal’s latest photography exhibit, “Can I Touch It?”. The series showcases white women sporting hairstyles that are traditionally thought of as “black,” in faux corporate headshots. After Slate published a gallery and article about the collection last October, the project has become a viral sensation—it was shared more than 70,000 times via social media even before its first official opening in March at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts and Culture, in Charlotte, North Carolina.

And what did Beal take away from what she calls the most personal work she’s done? “I learned that the experience I had as a minority woman in the workplace was the same as white women in their forties and fifties. We were all being judged on how we looked,” she says. “Opening that dialogue and realizing our experiences are universal was important. We think that these judgments are personal and intimate to us, but all people are going through the same thing regardless of race, age, sometimes even gender.”

The photo shoots took place last summer at the Center for Photography at Woodstock in New York, where Beal was in residency. After proposing the project, the Center gave her 100% support and use of their facilities to carry it out. Finding subjects to shoot, however, proved a bit more difficult. “I definitely got a lot of ‘no’s,’ to the point where it became a running joke: ‘how many will we get today?’” So Beal took to the streets—literally. “I just went up to people, introduced myself, and asked them if they’d like to participate,” she says. “When one woman would say yes, she’d tell her girlfriend about it, and it snowballed.” Other participants came through recommendations, and some were Beal’s actual former co-workers.

Because Beal was on a budget, she styled many of the women herself—and called on some friends to help set the cornrows, finger waves, and braids featured. Subjects didn’t have a say in their styles. “It was the ultimate form of trust especially considering I told them, ‘You’re going to get a random style, and it’s probably going to be different from anything you’ve ever had, and then we’re going to take your picture, even if you don’t like it,’” says Beal. “And some of the women definitely did not like chosen style on them.”

In fact, Beal has witnessed a variety of opinions on the photo series itself—some extremely negative, some positive, and a whole lot of humorous reactions, too.

“I wanted the humor, though,” she says. “Humor adds to the conversation because it’s ridiculous we create these stereotypes in the first place. If the topic is easier to digest with humor, then so be it,” she continues. “If people are talking about it, the project was a success for me.”

When the exhibit closes at the Harvey B. Gantt Center, Beal has an idea for a permanent location for the photos. “We’re looking at putting them in corporate spaces,” she says, laughing. “It’s one thing to talk about diversity in the corporate space, but it’s another to have it in your face.”

You Might Also Like

-

Inspiration

R&B Star LIZ Is A Blonde Bombshell Mixed With R&B Street Style. Rock Her Look.

- 185

-

Lips

How to Play With Different Lip Shapes à la Kevyn Aucoin

- 1117

-

Inspiration

Beauty Mood Board: Glamour Gore

- 38

-

Inspiration

Weird Finds: Kabuki Spa Masks From Japan

- 306

-

Inspiration

Vintage Inspiration: Michelle Pfeiffer in “Grease 2”

- 246

-

Nails

Nail Polish Inspiration from Fashion Week

- 27

-

Inspiration

How Bathroom Humor Helped Poo-Pourri Founder Suzy Batiz Find Success

- 537

-

Inspiration

It’s Take Your Vlogger to Work Day. We Shadow A Glittery Life to See How It’s Done.

- 272